The Wetlands Impact Tracker: Revealing Public Notices for the Public Good

Extracted from: https://www.policyinnovation.org/blog/wetlands-tracker

Original written by Gabe Watson (EPIC), Kumar Himangshu (MDI), and Matthew Vining (Atlas Public Policy)

In collaboration with Atlas Public Policy , the Environmental Data Impact Collaborative at Georg etown University, and Healthy Gulf , we built the Wetlands Impact Tracker . Using AI to extract data from US Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) public notices, this dashboard follows federal permitting developments and their impacts on sensitive lands and waters along the Gulf Coast.

How Does the Tracker Work?

Released in early 2024, the Tracker is a unique effort to extract and standardize information from the Corps’s numerous public notices. Covering four Corps Districts—Galveston, New Orleans, Mobile, and Jacksonville—the Tracker reveals notices affecting areas along the Gulf of Mexico dating back to 2012; over 6,000 of them to date.

For those unfamiliar with the Corps’s work, public notices are often the first opportunity a community gets to understand the scope and scale of a project proposed in their area. And while many federal (and local or state) agencies might be involved in permitting a project, the Corps handles permits for impacts—or benefits—to the “waters of the United States,” including our lakes, rivers, oceans, and wetlands. Known as a “404 permit” under the Clean Water Act, a notice typically describes the location, character of work, environmental impacts, and whether any mitigation is required to offset the projected impacts. Some public notices are for smaller-scale projects like a dock expansion or building a waterfront single-family home, while others entail hundred-acre refinery complexes and large residential subdivision developments.

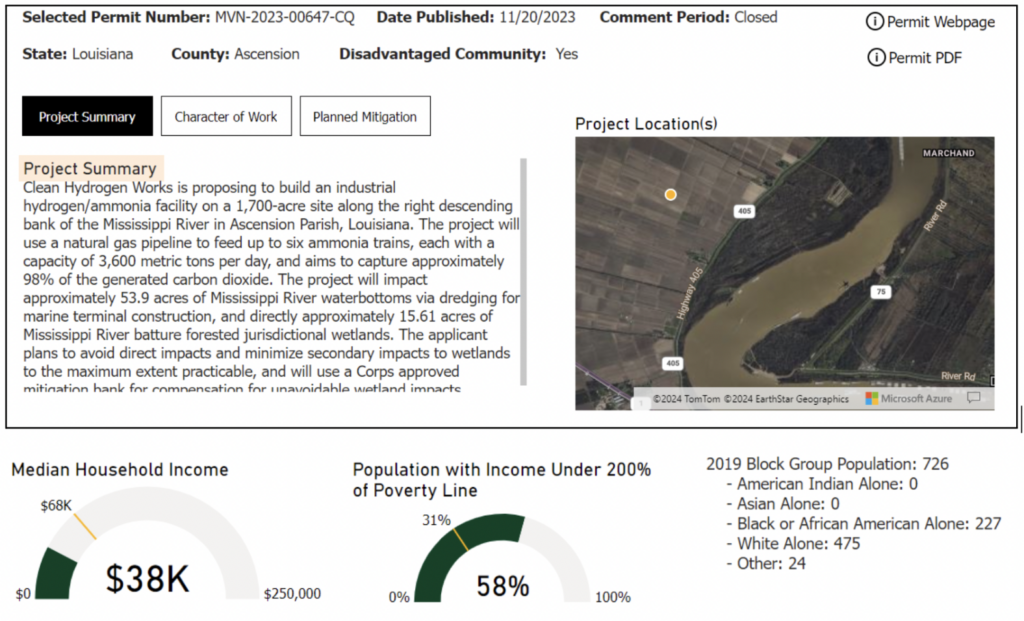

Screenshot of a public notice from the New Orleans District, 2023.

Why Did We Build It?

Sorting through the hundreds of public notices per year across the Gulf presents a massive logistical challenge for advocates focused on a small subset of those notices. For instance, only 6.5% of notices have been identified as Oil and Gas—presenting a “needle in a haystack” challenge. Significant Army Corps projects also present two challenges for society more broadly. First, the national No Net Loss of Wetlands policy, established by a 1977 Executive Order , mandates that any wetland loss must be counterbalanced by commensurate restoration efforts elsewhere, preserving essential ecosystem services. Tracking proposed and realized impacts from projects is a crucial component of ensuring No Net Loss. Second, projects can impact communities by exposing populations to hazards like noise and air pollution, in some cases permanently altering community landscapes, whether residential, rural, or industrial.

This Impact Tracker empowers advocates tackling both challenges by providing project-specific information like ecosystem impacts, location, and contact/public comment information. What’s exciting is that it also contextualizes notice information with community data, like disadvantaged status, income, and nuanced population characteristics. Filters allow users to find specific projects based on a variety of characteristics like county, date published, and a handy search bar to scan for specific text across all notices.

How Did We Build It?

Currently, the Corps publicizes notices as PDFs, via a web interface, requiring a user to click into each PDF to glean project information. The Tracker builds off the existing Corps system by gathering web page details and text from those PDFs. Using Artificial Intelligence (AI), we were able to create standardized, machine-readable data—cataloging things like project location, size, wetland impacts, project manager contact information, and public comment procedures. Once extracted, that data is then organized and displayed via the Tracker’s dashboard for easy searching and filtering, dramatically lowering the time and resources needed to identify projects of concern.

Because the data and implications of the Tracker cut across many domains—social, environmental, technological, and others—this work required an interdisciplinary team. Together with subject matter experts from Healthy Gulf, developers from Georgetown’s Massive Data Institute, and policy experts from EPIC and Atlas Public Policy, we were able to address the numerous challenges and decision points presented over the project’s six month time-frame. In addition, we sought iterative feedback from stakeholders and intended users during project ideation and development. And while those efforts took many rounds of review and validation, the project would not have been possible save for the breadth and depth of expertise across the team and key input from outside collaborators.

What Does the Data Show?

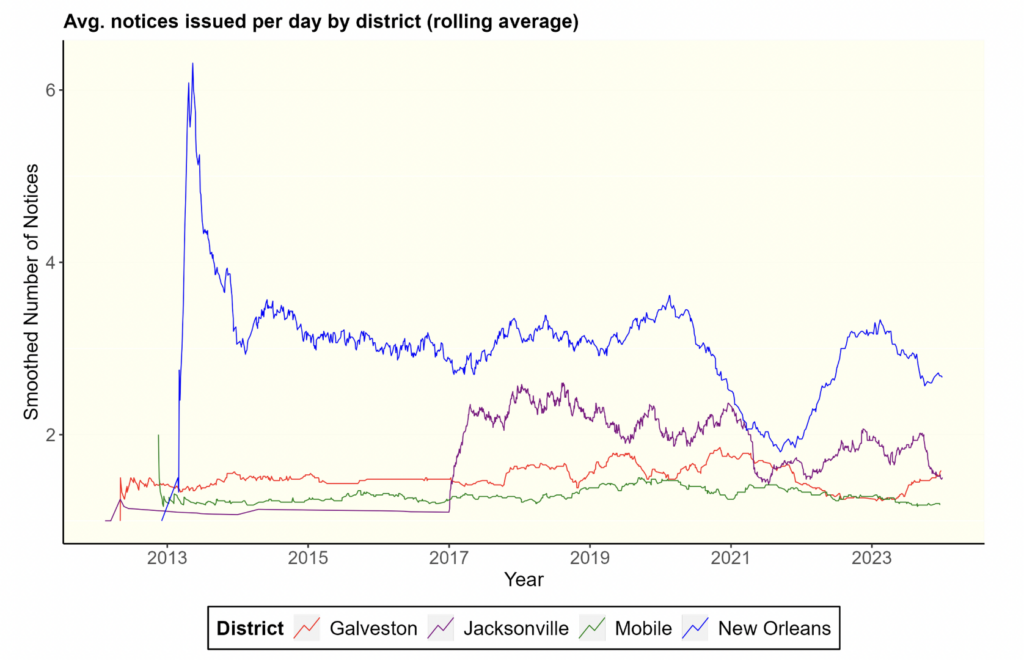

With some downstream data cleaning and analysis, we can harness a range of insights about the temporal and spatial patterns in project locations. For instance, the graph below shows that the New Orleans District historically had the highest number of notices issued among the four districts we evaluated, declining in 2022 before rapidly increasing again:

Plot showing the application of a 60-day rolling window to the daily number of notices per district, yielding the “smoothed” number of notices.

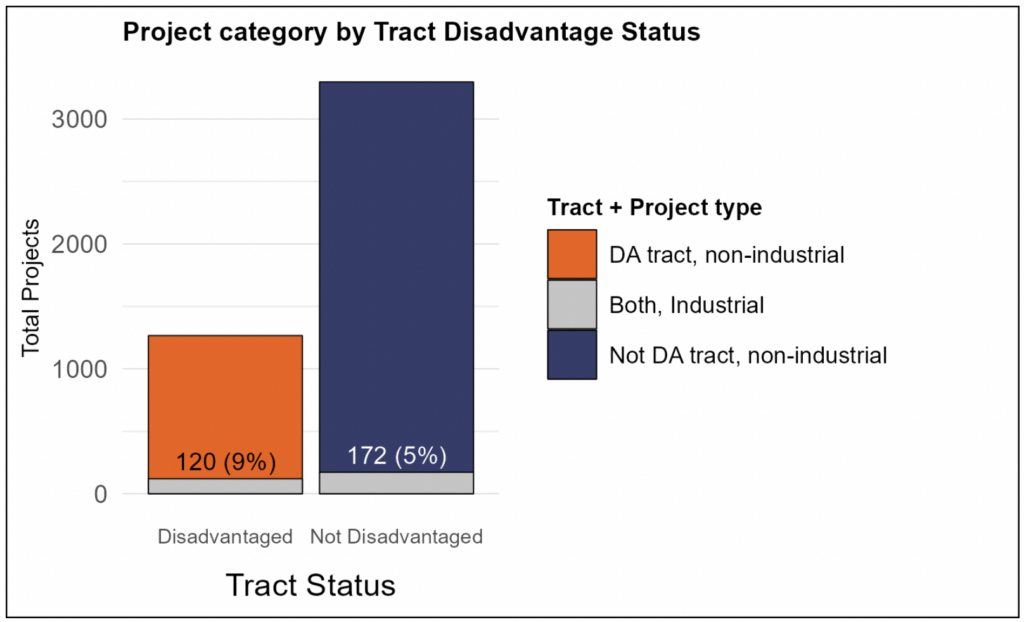

Our analysis—summarized more below—shows that a higher percentage of projects in disadvantaged tracts (9.4%) are industrial (largely oil or gas) projects, compared to tracts with a disadvantage score of 0 in the White House’s Climate and Environmental Justice Screening Tool (CEJST) (i.e., 5%).

A total of 1,651 census tracts intersected with project locations. Of these, 1130 had a CEJST disadvantage score of 0, and 521 had a score greater than 0. “Industrial” includes unique notice IDs containing keywords related to oil, gas and other infrastructural projects (assigned using keywords along with LLM classification).

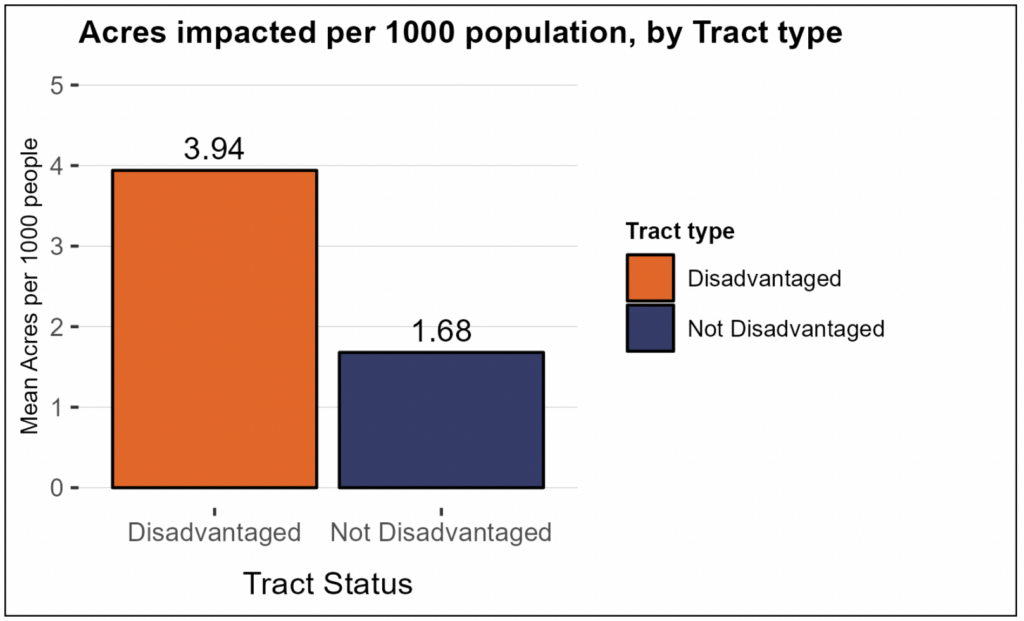

Y-axis shows the per capita proposed acres impacted for each category of tracts, scaled by 1000. The numerator includes the sum of acres impacted across all projects in tracts, the denominator, the sum of total population in tracts (for each category of tracts).

The highly granular nature of this data also allows us to look beyond macro-level insights—to narrow in on project types and details according to specific criteria. That’s a big deal for advocates trying to track impacts and numerous Army Corps projects across sensitive ecosystems, and often vulnerable communities.

A prime example of the types of projects the Tracker helps uncover is the Ascension Clean Energy Facility near Donaldsonville, in Ascension Parish, Louisiana, along the Mississippi River. The proposed plant will generate “21,600 metric tons per day of liquid ammonia,” and cover a total area of 1,700 acres—roughly twice the size of Central Park. Currently, that land mostly consists of agricultural and forested wetlands; but the project is projected to permanently impact 15.6 areas of protected (i.e., jurisdictional) forested wetlands, and dredge 53.9 acres of Mississippi water bottoms.

Data on this specific area drawn from other databases like Oil and Gas Watch and ClimateTRACE —shown below—indicate multiple proposed and newly built petrochemical projects in the region, ultimately supplying users a more comprehensive view of projects like this one.

Community Impacts and Cumulative Analysis

Along with directly threatening wetland loss, this project is also located in a tract identified as “disadvantaged” according to CEJST . Data from the U.S. Census displayed in the Tracker shows that the area’s poverty rate of 58% is almost double the national average. We can also tell that the affected area has seen significant population decline, with vacant housing units increasing by 28% across this tract between 2010 and 2020. Compounding socioeconomic stressors, the surrounding census tract sits in the 88th percentile for asthma rates and life expectancies—and is, on average, lower than 75% of the country, according to CEJST.

While this project proposes relatively large impacts to the environment and people, that fact is not unique. Our data shows that across all notices, petrochemical and industrial projects with significant environmental impacts like the ones we’ve sketched, are disproportionately sited in disadvantaged communities. Known as cumulative impact analysis, the Tracker enables this more robust vantage point across projects and time, helping users better understand complex patterns of development and their consequences, including systemic and disproportionate impacts on certain communities.

Lastly, under the National Environmental Policy Act , or NEPA, the Corps is required to determine “whether the action is related to other actions with individually insignificant but cumulatively significant impacts.” A recent ruling from the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals showed that the Corps failed to properly evaluate the immediate and cumulative impacts for a subdivision project along the Tchefuncte River, just 80 miles west of the Ascension Clean Energy Facility proposed site. With more (and more relevant) data from the Tracker, researchers and advocates will be better equipped to evaluate cumulative impacts like these at the community and watershed levels moving forward—ultimately, we hope, helping bolster arguments for increased due-diligence on the part of the Corps when considering new permits.

How Do We Use Large Language Models (LLMs) to Process Public Notices?

With that understanding of the Tracker’s role in understanding impacts across space and time, let’s dive into the mechanics of how we glean information across notices and Corps districts. At its heart, the Tracker is a bespoke PDF extraction tool that converts text into structured dictionaries—and then, into tabular data.

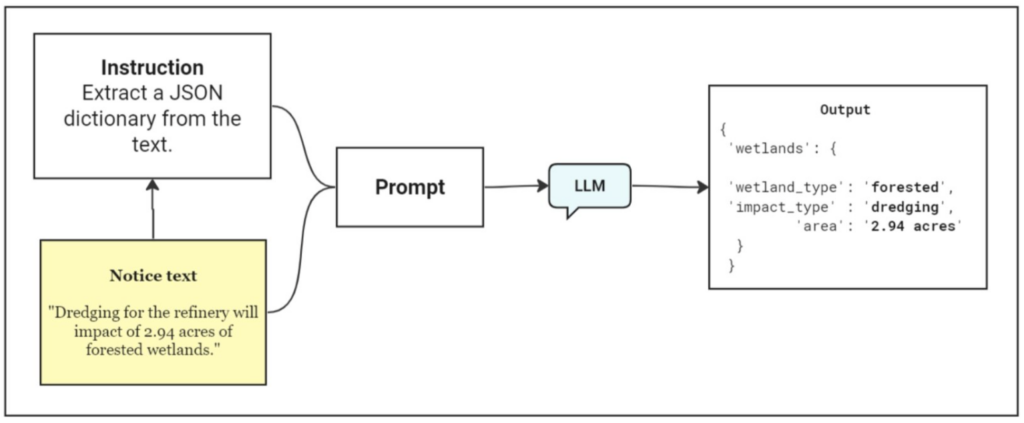

The use of large language models (LLMs) to generate machine-readable information from unstructured text is rapidly emerging as a viable use case. The following image shows an example of such a workflow: the prompt consists of an instruction (“extract topics in JSON”) and the text on which to apply the instruction. The expected output is a JSON-like structured dictionary of the topics in the text.

Depiction of workflow.

The traditional alternative to natural language processing (NLP) methods for this problem would be regular expressions (regex). This approach is set up to extract strings from text, based on explicitly defining all possiblepatterns to identify our key fields (e.g., an instruction like “extract the number before the word ‘acres’”). They do perform accurately on a large number of notices, but this requires us to specify any pattern that may occur in future notices.

However, an LLM with sufficiently generalized capabilities can extract the key attributes, augmented by external libraries that can constrain the LLM’s generated output to a specified format—usually JSON. We use OpenAI Function Calling to specify the required schema for the Tracker, but multiple open-source libraries designed for this task have become popular (e.g., Instructor or Outlines). This does not mean the LLM performs with 100% accuracy in extracting wetland impacts—and we are currently exploring ways to improve model outputs by “fine tuning” the model to perform better in our specific use case. Still, it illustrates how AI tools can deploy near-human level reading comprehension with speed at low cost, thus allowing advocates to monitor—and respond—to far more information than was feasible previously.

Looking Ahead

We think the Wetlands Impact Tracker represents a significant advancement—not just for monitoring, but also for understanding the environmental and social implications of projects affecting wetlands and water bodies along the Gulf. By extracting and standardizing information from numerous public notices, this tool can provide valuable insights into the scope and scale of many projects, ranging from minor developments to large-scale industrial endeavors.

What’s more, the Tracker not only facilitates the identification of projects of concern, but also supports efforts to achieve key national environmental goals in service of the public good—like No Net Loss of Wetlands. It likewise empowers advocates and researchers to address socio-economic disparities using cumulative impact analysis. And while the Tracker is already providing value to advocates on those fronts, rapid advancements in text extraction technology also present new possibilities for model improvements. Looking ahead, we hope to expand the Tracker’s reach to additional Army Corps districts, and make connections to other platforms like the Environmental Integrity Project’s oilandgaswatch.org .

If you find yourself using the Tracker in your work—or if you have questions or feedback on the tool—drop us a line. We want to hear from you! To learn more about the Tracker, check out a recent webinar we hosted here .

Special thanks to Kumar Himangshu (MDI), Matthew Vining and Mohit Mendiratta (Atlas Public Policy), and Scott Eustis (Healthy Gulf) for their work on this project.